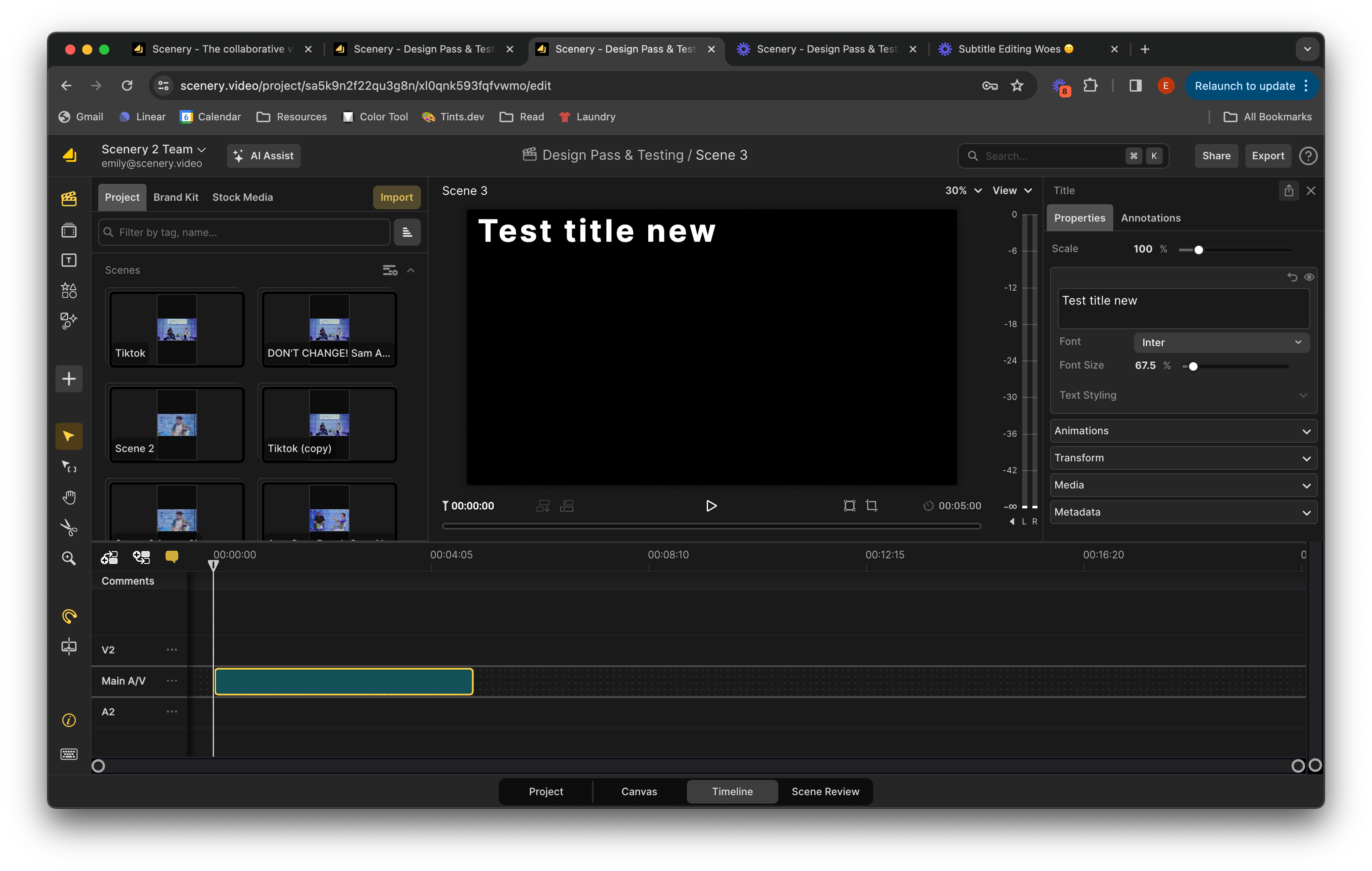

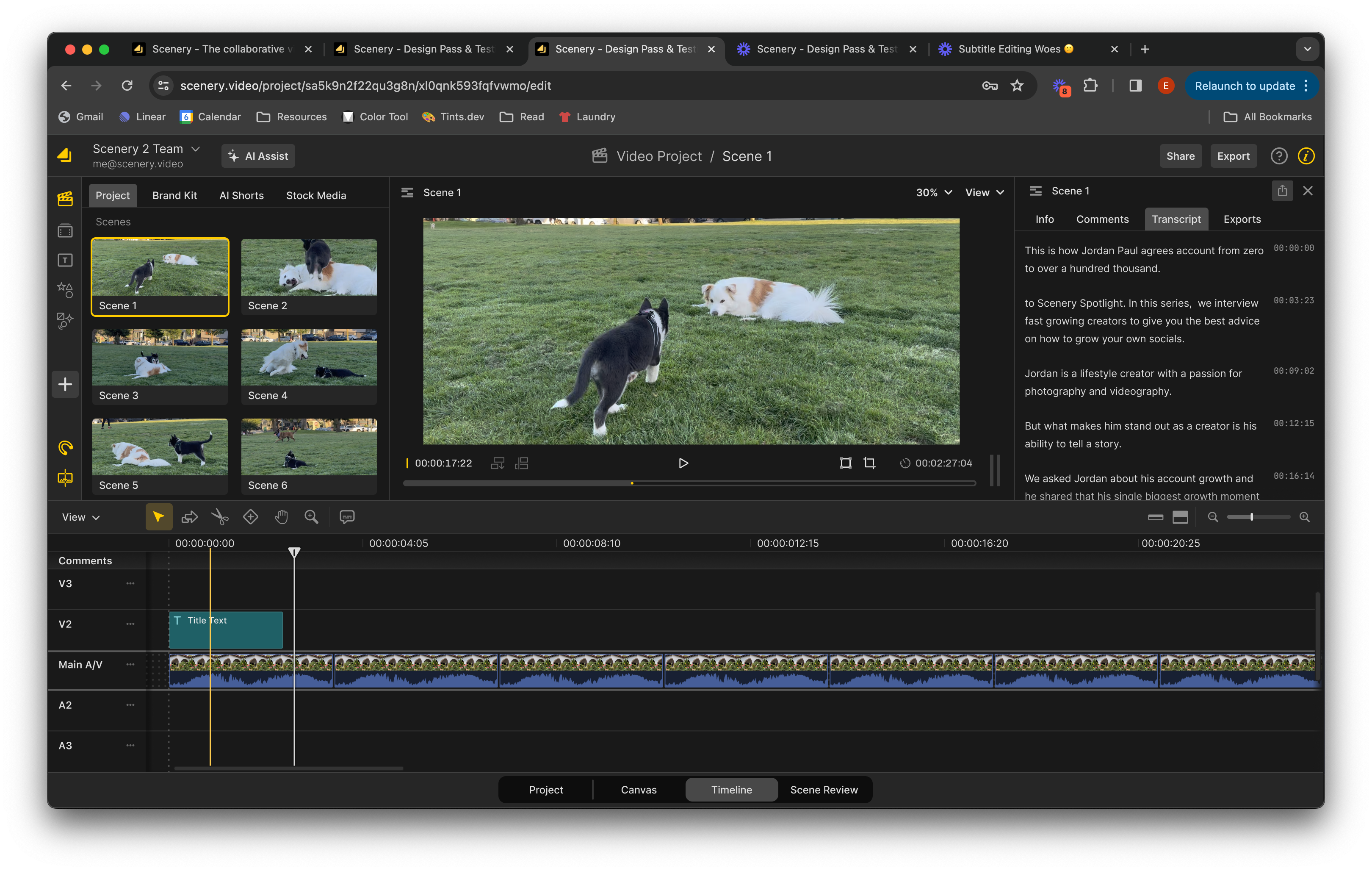

Scenery is a real-time collaborative video editing web application, almost like FigJam for Final Cut Pro X. The company has since been acquired by Adobe.

Background

When I joined the company as their only full-time product designer, I inherited a design process that had been pieced together by a front-end engineer without formal design training, supplemented by occasional input from Final Cut Pro X team contractors. There wasn’t a cohesive design process or a clear understanding of who we were designing for. One of my favorite projects was tackling the timeline — one of the most heavily used parts of the product, and also one of the most frustrating.

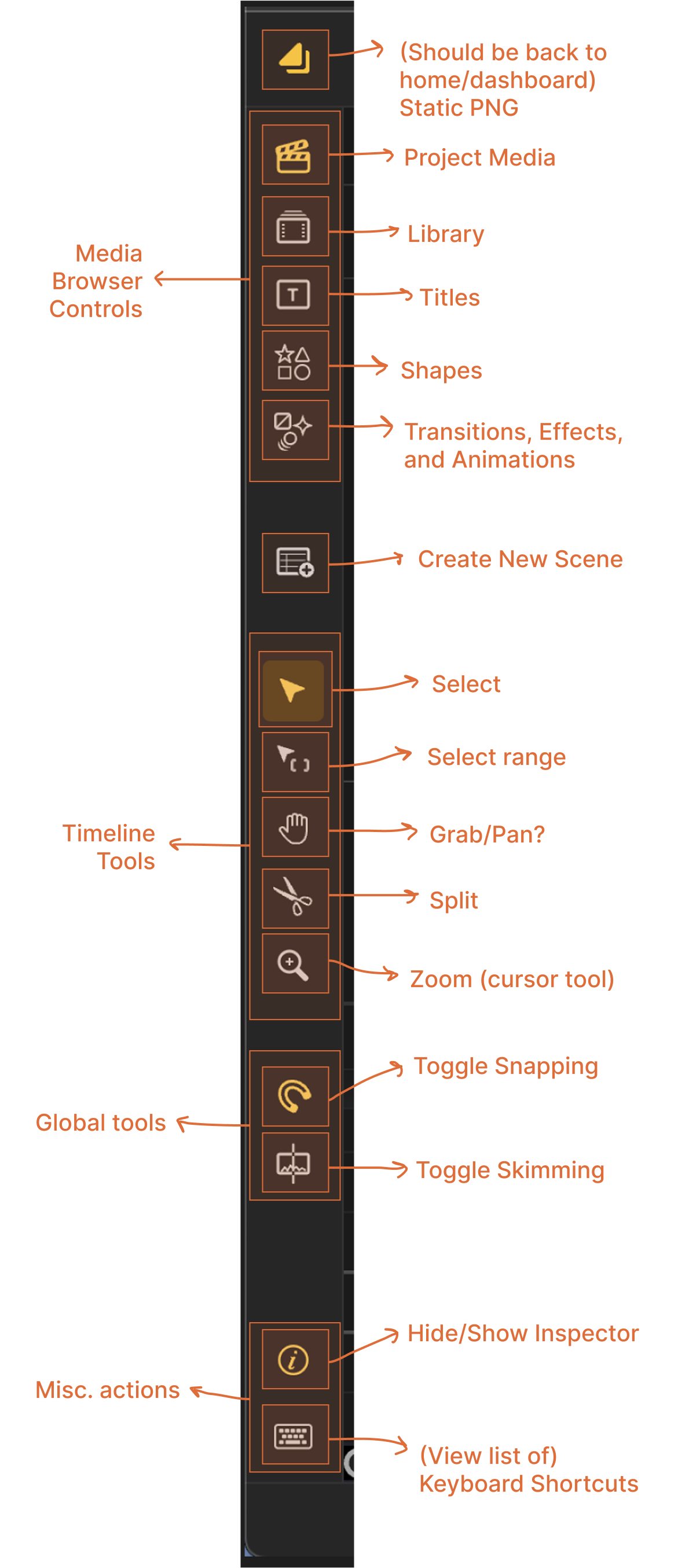

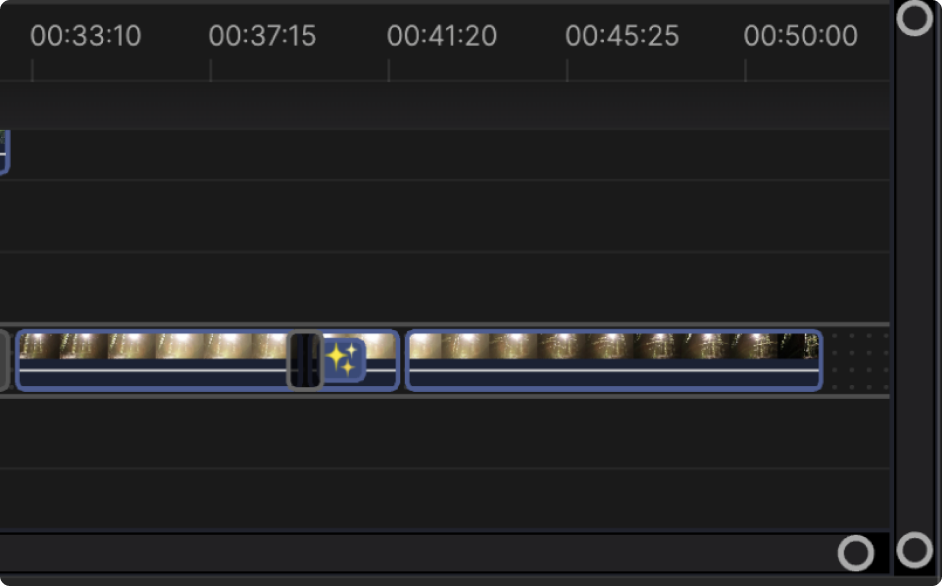

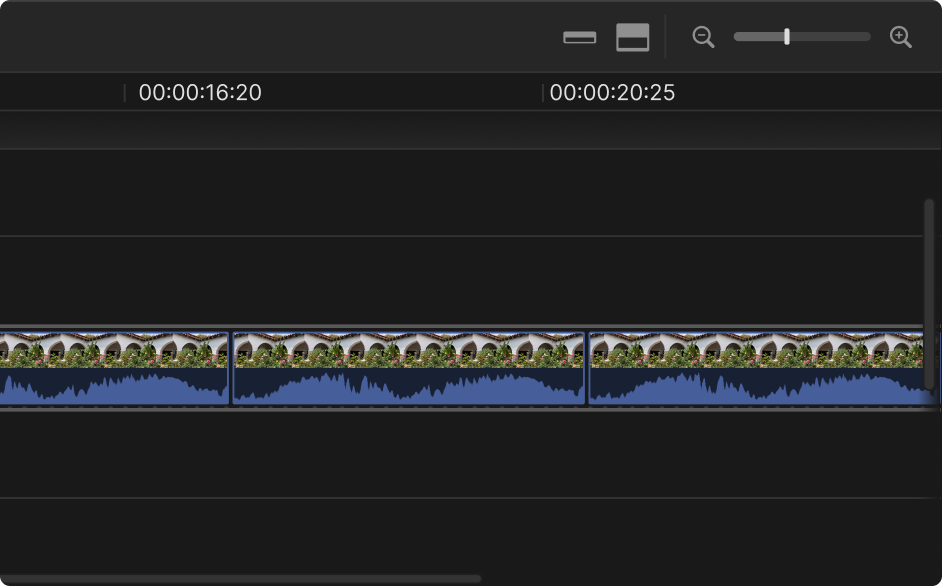

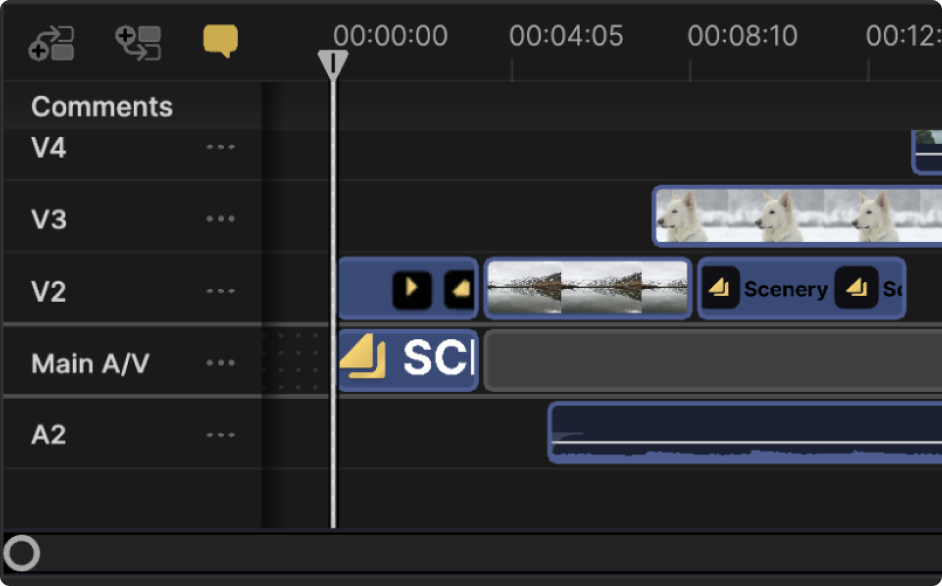

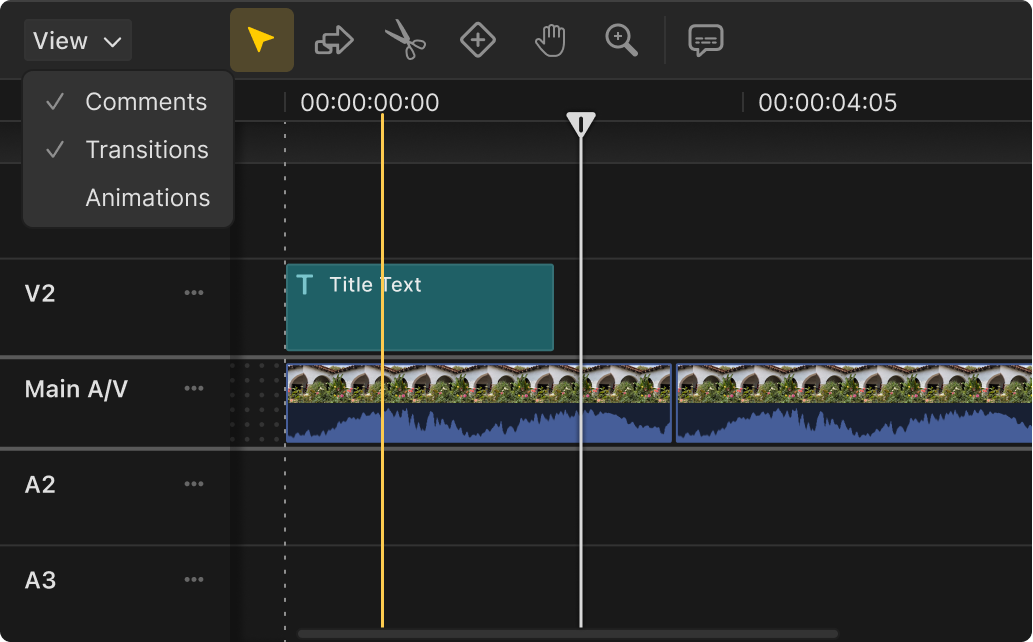

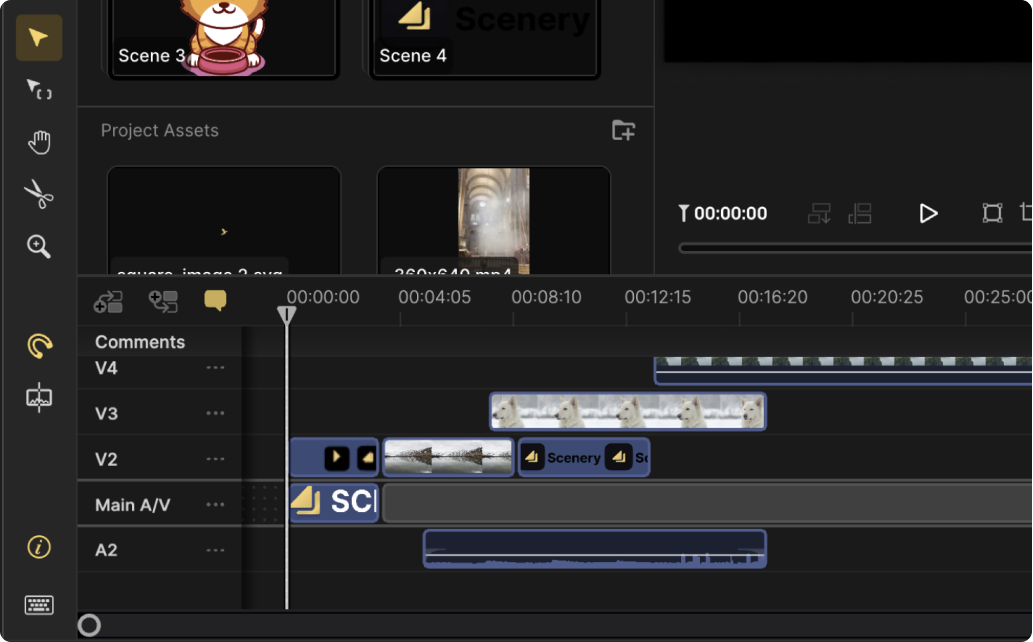

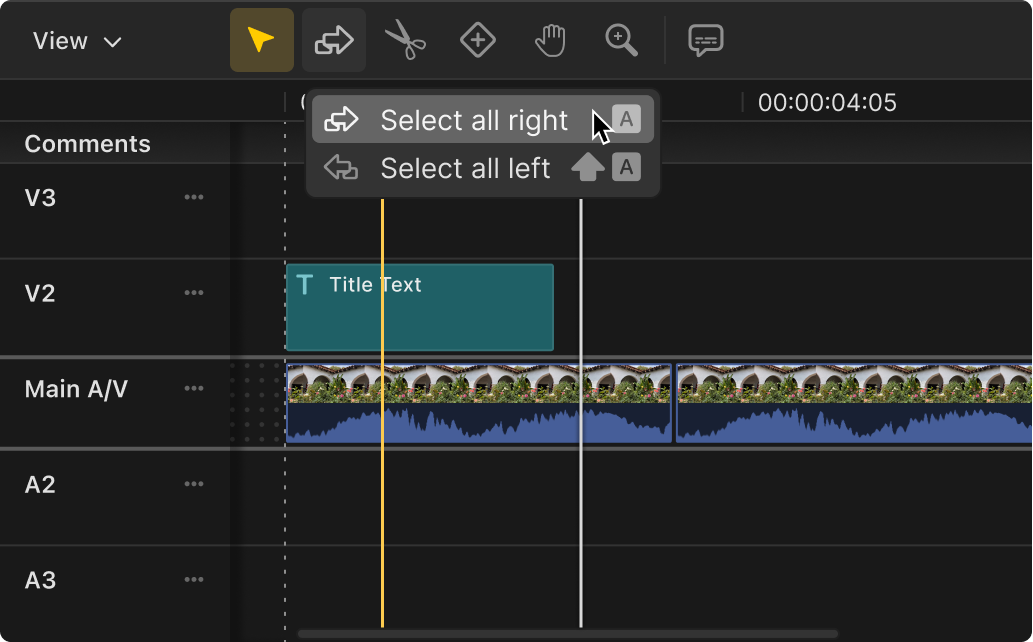

Scenery’s editor had grown organically over time. The toolbar was filled with a mix of tools and filters that weren’t organized in any logical way. The timeline was filled with problems. Many of the features regularly used by professionals weren’t discoverable, adding transitions or animations made it impossible to adjust audio levels on a clip in the future, and if you happened to bump your trackpad or scroll while inside of the timeline, you would lose your place and completely change the vertical and horizontal zoom of everything inside.

Employees had been pushing for a modular version of the application for a while, but it wasn’t until a hack day — when an engineer named Jay created a working prototype (in a day!) — that the idea was given the go-ahead. His proof of concept created a window for me to step in and take the redesign from idea to implementation while improving the editing experience for our users.

the project

A modular redesign of the video editor’s timeline — initiated, researched, and designed solo to improve clarity, reduce clutter, and create a foundation for future growth.

Identifying problems

To begin, I set up time with my coworkers, especially subject matter experts with experience in professional video editing, asking them to show me their editing process. I made it clear that I wasn’t here to judge or defend the product. I just wanted to hear what was working and what wasn’t.

I also reviewed open tickets related to the timeline, explored past design files to understand what had been tried and why it might have failed, and reached out to coworkers who were experienced editors. They walked me through their workflows in tools like Avid, Resolve, and Final Cut, which gave me valuable context for what professional editors expect and rely on.

Along the way, I kept returning to a core question: who are we designing for? I asked leadership for clarity on our target audience, but they were reluctant to define one. So, I chose to focus on improving the experience for the users we already had — creative professionals who needed a powerful, flexible editing interface that could also support newer users without being overwhelming.

Side tangent... My take on user research

When doing user research, I’m careful to pay attention to what users seem to have trouble with, points of friction, and work to understand the problem for myself before asking users themselves for solutions. I believe that a fresh perspective on an issue, coming from a place of wanting to make their lives easier and facilitate these super talented people, allows me to identify and diagnose issues with the user experience that prevent it from seeming second nature or intuitive.

My goal when designing a product or feature is to have the user eventually find the tool themselves without guidance or agitation. I want their experience to feel like walking into someone’s well-designed kitchen and finding everything you’re looking for in the first place you check.

When I conduct any user research, I like to give them a task to accomplish, sometimes broken into steps and phases as needed, and sit quietly and watch them work while they walk me through how to do things. By doing this, I’ve been able to identify workarounds and unconventional ways users have figured out how to use the product that they might not explain to me otherwise. I can see when they automatically mouse over to one side of the screen to click a button, only to hesitate when they don’t find what they’re looking for. In my experience, users don’t like making mistakes in front of others and often feel uncomfortable complaining about things if they think the researcher designed it.

I like to start these sessions by telling users something along the lines of: “I would just like to say before we begin, that this product is supposed to be designed for human beings like you. You can’t mess up here. Any mistakes you think you make are really mistakes that we have made. It means we have improvements to make.”

Problems identified

Through conversations with editors, review of design files and support tickets, and observation of real workflows, I identified several recurring problems in the timeline interface. These issues ranged from tool discoverability to unintuitive interactions and layout constraints that made the editing experience feel clunky and frustrating.